Cookbook Review: Hawker Fare

Written by: Lasamee Kettavong

Edited by: Dorothy Culloty

Photo by Studio Guile/Carrie Crumbley

Cooking techniques passed down from our families, near to our hearts and welcomed by our stomachs are nearly perfect to us in every way without reservation. We are comforted by the familiarity and the memories that these meals give us in addition to doing the important work of sustaining our beings.

To me, the most important thing that these inherited cooking methods are missing is exact measurements. The palm of your mom’s hand for salt is probably similar but not exactly like my mom’s. The count for bird’s eye chilies in your dad’s tum makhoong (fresh, funky, spicy, and sour papaya salad) could differ by a lot from my own family’s recipe, depending on which sibling is cooking. While these differences are to be celebrated, honored, and cherished, it’s helpful to have measurements as a guide for someone new to the recipe, who never learned how to cook from their family, or anyone looking to feed as little as two people or as many as 30 without accidentally wasting ingredients.

Photo by Lasamee Kettavong

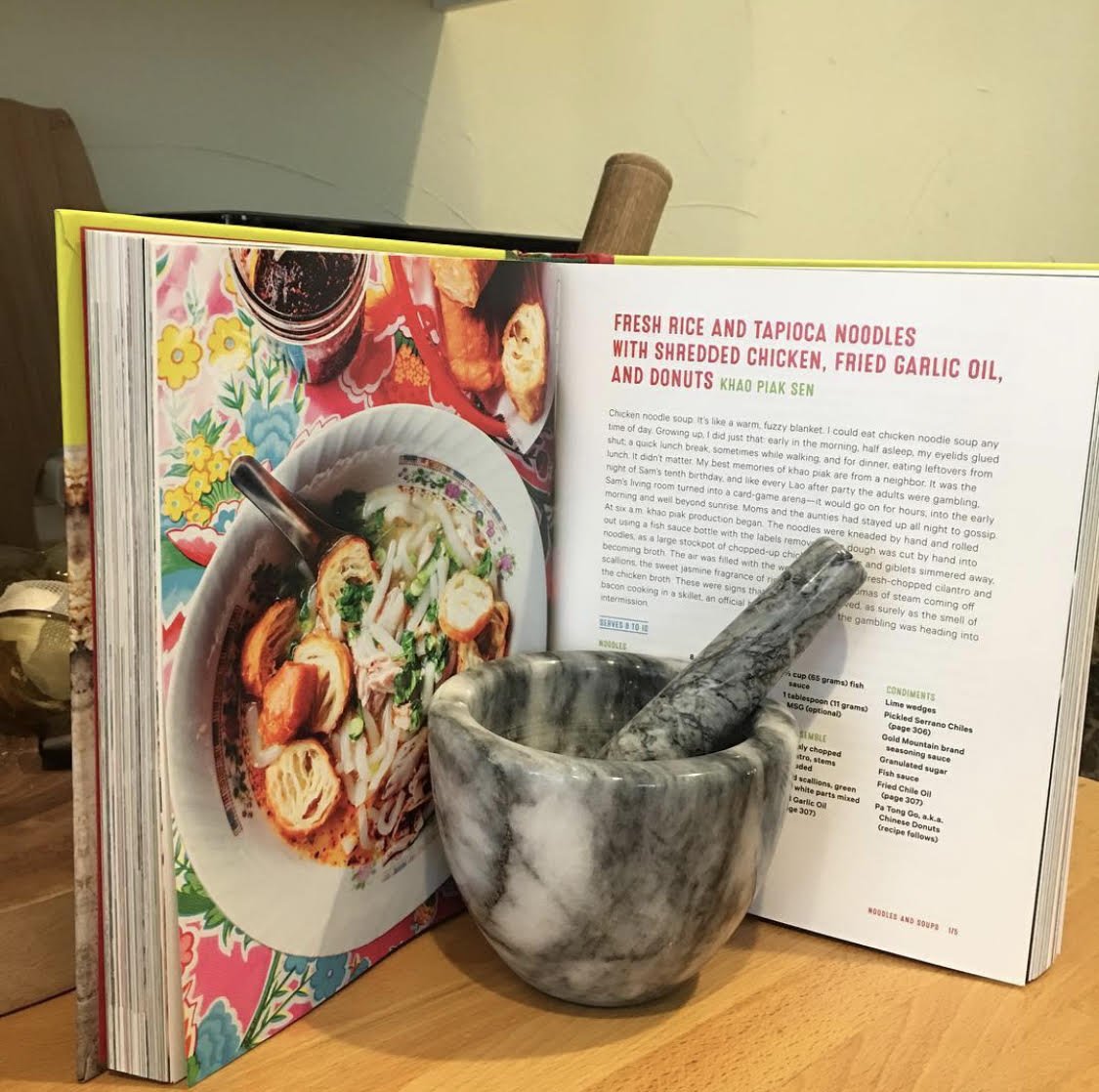

This is one of the many reasons why I love Hawker Fare, Chef James Syhabout’s cookbook on Lao food; he enables someone like me, a first generation Lao American woman who really wants to cook and share Lao food with people, to figure out just how much sticky rice to soak and how many pounds of what protein I’ll need to feed just myself and my partner as opposed to cooking how my mother would for a family of seven. Plus, the recipes are easy to follow and accompanied by bright and gorgeous photographs that showcase the beauty that is a Lao food spread. I had never made khao piak sen (hand-cut rice flour and tapioca noodles) before since my mother typically bought them from the Lao store when I was a child, but the recipe and instructions in Hawker Fare simplified the whole process. “Cut off a piece of dough the size of a tangerine and start rolling the noodles either in a pasta rolling machine or with a rolling pin. Roll the dough about ¼ inch thick and 2 inches wide. Stack the rolled dough pieces with a dusting of tapioca between each so they will not stick to one another.” Chef Syhabout answers all the questions that might come up when you’re making these noodles before you can ask them: what size should I cut the dough? How thick should it be? How do I treat these sticky, starchy dough sheets? Now I make these noodles every year around New Year’s day (January 1st in the U.S.), a mindful practice that results in a delicious, comforting meal to celebrate a new beginning.

When I asked Chef Syhabout how he felt about the impact of Hawker Fare along with sharing my own thoughts about it, he responded “Little did I know or think about how the Hawker Fare cookbook would be received at the time of conception to publishing. I am glad I was given the opportunity to share my story and Lao cuisine that has touched so many Asian Americans especially in the Lao community that had very parallel upbringing and food experiences. I am hoping my story will spark more interest in Lao food in the mainstream as it deserves to be.”

Photo by Studio Guile/Carrie Crumbley

Perhaps apparent in his response to my question, What drew me in and had me reading part one in one sitting was Chef Syhabout’s voice, which flavors every part of “Hawker Fare.” The book begins with stories, both his as well as the shared experiences of Lao refugees. This is followed by recipes of the food that he grew up eating, and that comforts Lao people who have been resettled in the U.S. Broken into these two major parts, Hawker Fare is unified by Chef Syhabout’s vibrant and loving descriptions of the food and the context in which it was prepared and enjoyed by the community. His writing is conversational; he’s immediately your ai James (older brother, in Lao) joking around and making you laugh. You want to sit down at the pa khao (traditional low, woven, bamboo table) with him and catch up over khao niew (sticky rice), seen savanh (heavenly beef jerky), and a tum of some kind.

The Lao and Isan pantry section in the book was a delight to peruse, as so many of the sauces were the ones that I grew up with but couldn’t find on the shelves at the regular grocery stores in my neighborhood. If you haven’t had a hard boiled egg doused in Golden Mountain Seasoning sauce (it’s like soy sauce but better), then you should correct that situationsituation toute suite. You’re guided by Chef Syhabout to inspect the labels on the sauces, as he advises that if the label indicates that it was made in Thailand or Vietnam, “it’s probably legit.” You can bet that a Lao person will have at least a couple, if not all of these goods, in stock. These ingredients include toasted rice powder (homemade from glutinous rice), Formosa Pork Fu, or Chinese pork floss for jaew bong (Lao caramelized aromatic chile dip), naam pla (Tiparos or Squid brand, though in the Kettavong household, we always had Lucky brand), padaek (fermented fish sauce, Pantainorasingh brand), and Golden Mountain Sseasoning sauce. These pantry essentials distinguish Lao food from other southeast Asian cuisines.

Photo by Studio Guile/Carrie Crumbley

This is something that Chef Syhabout addresses that is important to note: many Lao dishes are similar to Thai dishes and are often labeled as such. And the history behind “How Lao Morphed Into Thai” is a complex one that Vinya Sysamouth, co-founder of the Center for Lao Studies in San Francisco, begins to unpack in a conversation with Chef Syhabout. Sysamouth details the complex history of the three ancient kingdoms that became Laos during French colonialism in the region. How ethnic Lao, who were living, working, cooking, and shared their food in Thailand. And finally, how Lao food came to be presented in the US as Thai food, as it (Thai food) became popular in the 80’s and 90’s. Such dishes as the beloved national dish of Lao, laab, a hearty minced protein salad mixed with roasted rice powder, spices, and aromatics and scooped up with steamy sticky rice, is often mistaken or labeled ‘Thai.’ Lao refugees in the US faced many challenges, and one of them continues to be reclaiming the food from the motherland.

Chef Syhabout writes about what was common across the Lao refugee families with whom he grew up: what was familiar, what was different but quickly became adapted (like Uncle Ben’s rice packets in place of jasmine rice and Spam for protein), and the ingenuity that comes with being presented with limited ingredients but thankfully being a “cook to the core.” It’s clear that the community, despite being thousands of miles away from a Mekong River market, still operated as if they were shopping on the banks or on river boats, trading ingredients and meals for those pantry essentials, each person having a specialty or skill that complemented their neighbors’ abilities and offerings.

Not only does Chef Syhabout write about the Lao community, but he also reminisces about trying American barbecue for the first time with his neighbor, Harold, “a man like a muscular wall … who [he later discovered] was an original Black Panther.” He paints a picture that I see in my mind’s eye: trying food from a culture different from one’s own heritage and falling in love with it. This is my hope for any new tasters of Lao food.

Photo by Studio Guile/Carrie Crumbley

As a reader and first generation Lao American woman, reading Hawker Fare legitimized my experiences growing up. Chef Syhabout steps back from his personal story to write about Lao culture that enables people like me to feel seen and acknowledged, as well as accepted. In one of the call-out pages (pages that include information tangentially related to the stories or the recipes), Chef Syhabout writes about family and friends sharing a meal, titling the piece “One Bowl, Many Salivas: The Art of Communal Eating,” because traditionally Lao folks used to literally eat by “dipping into shared dishes … Double dipping makes everybody around the table or saat equally vulnerable - you need trust to eat so intimately.” It’s something that my family still did here in the states as I was growing up and that didn’t seem odd to me until the idea of “making a plate” or having individual servings came into my world via my siblings’ partners, my in-laws. It’s affirming to see yourself in the pages of a book when you have felt and lived between two worlds your entire life. I had an “aha” moment reading that story - it wasn’t just my family practicing this kind of meal sharing; it was part of the culture I was finally discovering. I ate up every word.

Perhaps my favorite take away from Hawker Fare is the idea that "cooking with instinct, or refinement, isn't always better," advice from a renowned chef, which empowers the home cook or someone new to Lao cuisine. I firmly believe that a meal can be technically perfect and impeccably prepared by a Michelin star chef, but it will definitely taste different, perhaps digested just a bit better, when you have been able to prepare the same meal to share with friends, family, and loved ones.

Follow along with Chef Syhabout on instagram