Review of Le grand livre de la cuisine asiatique

Written by: Lasamee Kettavong

Edited by: Darby Dyer

Photo: Lasamee Kettavong

I always visit the cookbook section of a bookstore, no matter where I am. Whether it’s where I live, Denton, TX, or where I’m visiting, which so happened to be Montreal, Quebec, this time. It was a rainy day, so my partner and I dodged into a welcoming bookstore off the stretch that we’d been walking on to warm up and get a feel for what an independent bookstore in a different country might be like. I headed straight to the food and dining shelves of course. I write cookbook reviews specifically about Lao cookbooks and those that include Lao recipes because it’s still so rare for you to find one on the shelves at any store you walk into. So I choose to point out and emphasize the time and place the cookbook was written, the authors and contributors, and the context of the Lao portions of the cookbook. Oddly enough, there were two versions of this book: one that was a little less intensive and didn’t include Laos, and of course, the version that ultimately piqued my interest.

I snapped a photo of the cover and let the copy I’d leafed through remain. Months later, I came home from a short weekend trip and the book was on my coffee table. A gift from my thoughtful husband who’d noticed it on my Amazon shopping wishlist. It was a sweet reunion (though I knew that it wasn’t the exact same copy that I’d picked up, it felt close enough).

Photo: Lasamee Kettavong

Because food and culture are inseparable from history, this cookbook review warrants a note about the history between France and Laos and of Indochina. The intertwining of their histories, however, is present to this day in the geographic locations of Lao people, in the language (note, how, even in French publications, Lao words remain as the choice term or phrase), in the food (condensed milk and french bread as a dessert, anyone?), and in the land.

“For half a century Laos was a colony of France. But from the time of conquest, an ambiguity lay at the heart of the French presence in Laos…French interest in Laos was always in relation to somewhere else. The expedition of Doudart de Lagree and Francis Garnier was undertaken to discover a ‘river road’ to China. The goal of August Pavie and other French imperialists of the late nineteenth century was to extend French jurisdiction over as much of Siam as possible. Their real interest lay in the rich and populous territories west of the Mekong: Lao territories on the east bank which could be claimed in the name of Vietnam were annexed merely as a springboard, and to gain control of the river itself. For colonial governors of French Indochina, the value of Laos was primarily as a resource-rich hinterland for Vietnamese settlement and French exploitation, neither of which took place either in sufficient numbers or with expenditure of sufficient capital to produce revenue enough to cover administrative costs” (20).

Photo: Lasamee Kettavong

I make note of this because it’s impossible not to with this cookbook review, Le Grand Livre de La Cuisine Asiatique (2015), because it’s written in French.

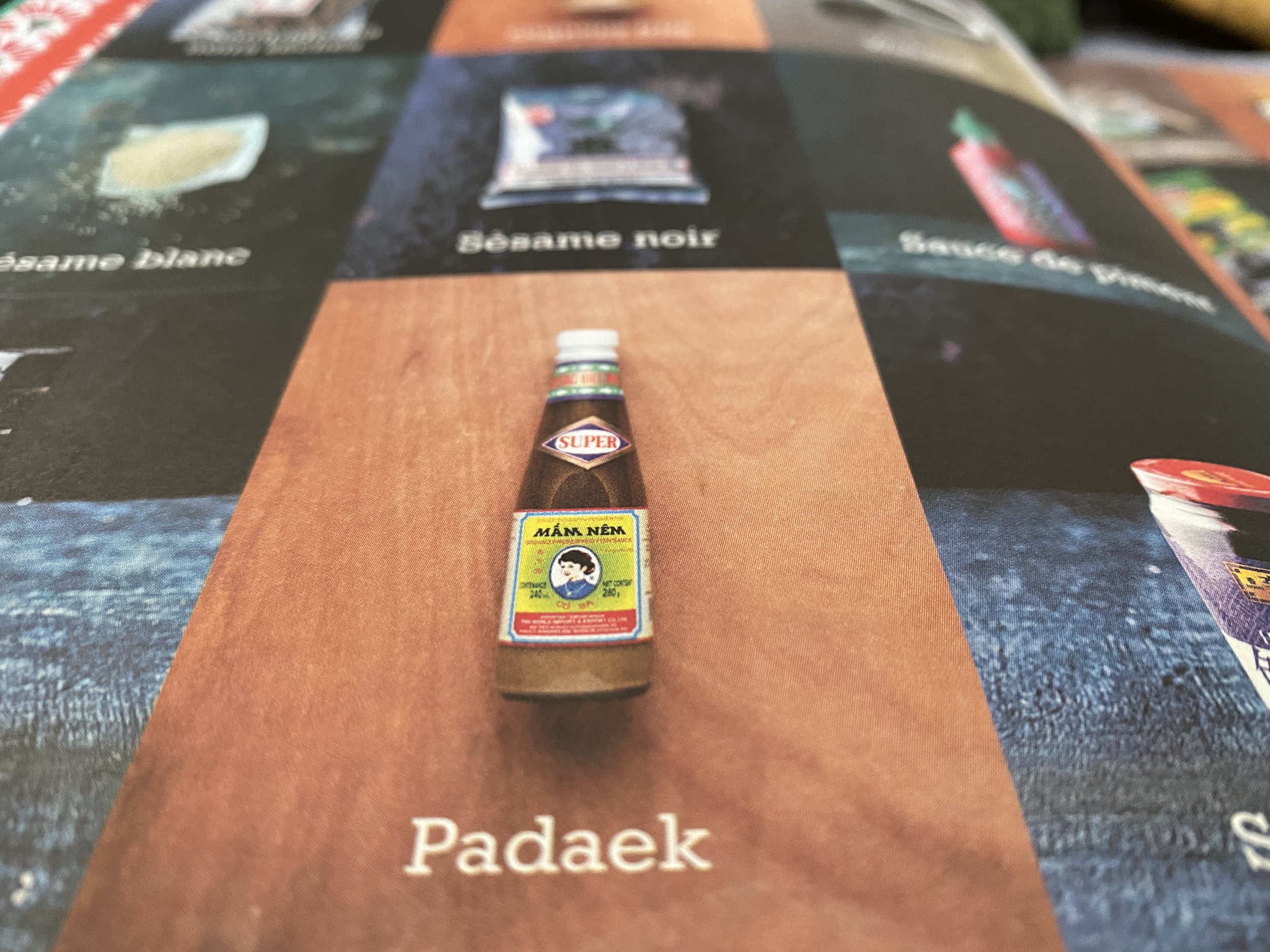

This cookbook is organized by dish type (les entrées et hors-d’œvre, les soupes, les salades …), then labeled by country of origin. Like many cookbooks for the 21st century, it’s filled with beautiful photography of the ingredients and the prepared dishes. Le Grand Livre… starts with a few pages of curated, essential ingredients to a well-stocked pantry. Some ingredients are listed in French, and some are distinctly, heartwarmingly-familiarly listed in Lao. It feels good to be seen. There is also a section solely devoted to sauces, which in any kind of cooking can be the star of the dish or the handy sidekick.

Before the main part of the cookbook begins, where different kinds of dishes make up the category sections, there is a fact sheet on how to use a wok, considered a must-have tool for Asian cooking. I appreciated seeing this handy pan highlighted as well as recommendations on how to choose one if purchasing.

Included in this book are the traditionally common recipes that involve noodles and rice, like khao poon nam kai (curry chicken broth with vermicelli noodles) and khao piak (rice noodle soup). One of the recipes I was most excited about was liserons d’eau sautés; khoua phak bong is sauteed water spinach. I’ve never seen this recipe before in a Lao cookbook or cookbook that includes Laos, so coming across it was a delightful surprise! It’s something I remember eating as a child but didn’t know how to properly describe it to my mother or make it.

Photo: Lasamee Kettavong

It seems there is less story-telling and narratives prefacing the sections in this cookbook, but it reminds me somewhat fondly of the objectives in a college seminar class, where you learn a little bit about each concept on which you could do a deeper dive on your own or later in your education. Each “concept” equates to a country in this case and is noted in the index; however, I can only assume that the individual cookbooks from which this book extracts recipes contain the anecdotes and stories that we commonly associate with family dishes and the like.

Perusing the index, I found the sources of all the recipes listed, and coincidentally, the Lao recipes were all extracted from Easy Laos by Vimala (Vim) Vilaihongs-Vallée, with whom the Lao Food Foundation had conducted an interview prior to my knowing this. The sweetest coincidence, I thought.